Part 2: The Latest Imperfectly Well Balanced Climate Policy Book

In This Edition

- Breaking Down Buy Clean Procurement Policy

- The Importance of Permitting Reform

- Ways The Big Fix Was Flawed

- An Exercise to Help Launch Your Climate Career

- Calls to Action

Welcome back to the newsletter and happy holidays! With COP27 now over, let’s resume recapping The Big Fix; this time with some perhaps unexpected twists. Please note this piece is longer than usual to account for the delay in posting time compared to Part 1. If you’re new to following Climate Ingenuity or otherwise missed that piece, check it out here.

First, two more key climate solutions:

Adopt Buy Clean Policies Widely

Of the five major economic sectors that contribute to climate change, arguably the hardest one to decarbonize is industry. Not only do current processes burn a lot of fossil fuels, but in some areas like cement, emissions are inherently embedded into their chemical processes. Overall, this sector produces roughly 30% of global emissions annually as of 2017.

There are at least three fairly straightforward types of solutions for industry the authors cover: efficiency, fuel switching, and reduced demand. None will completely slash emissions by themselves. However, the authors highlight one overarching policy that has the potential to apply the best of them all: buy clean procurement standards. Simply put, this means governments purchase construction materials with lowest emissions possible, accounting even for those coming from supply chains. Already the Biden administration has announced multiple actions involving this policy, and several countries across the EU have passed similar ones as well. Thus, Hal and Justin say the challenge ahead is to adopt Buy Clean more globally and across all levels of government, especially within the top 20 emitting countries.

Permitting Reform is Critical

Out of all barriers holding back climate progress in the US, NEPA in its current form might top the list. Shorthand for the National Environmental Policy Act passed in 1969, it requires agencies to review potential effects proposed projects have on the environment before permits for them can be approved. Although perhaps created with good intentions back then, unfortunately nowadays it’s widely misused to block or delay clean energy from being built (transmission lines, offshore wind, etc). Reports have also surfaced that fossil fuel companies have secretly been exploiting NEPA to widely fund lawsuits local residents file against said projects.

So what can be done about this? Permitting reform is a complicated topic, hence why it’s received so much national attention lately. The authors do however advocate for two changes to start: First, strict time limits for review processes, and second, shorter time windows for opponents to file lawsuits so projects can get done in say 2-3 years rather than 10-15+.

The limiting factor may well be it’s likely only Congress that has the legal authority to tackle this issue. Ultimately though, it’s imperative that NEPA is reformed as soon as possible, as we can’t let largely misinformed local groups undermine the best interests of the country on climate.

Overlooked Flaws

Although I enjoyed The Big Fix and found it easier to read than other climate policy books, there were some parts where I disagreed with the author’s points of emphasis. They’re also not the only ones making these mistakes. Allow me to explain:

Falling Cost Isn’t The Best Metric of Progress

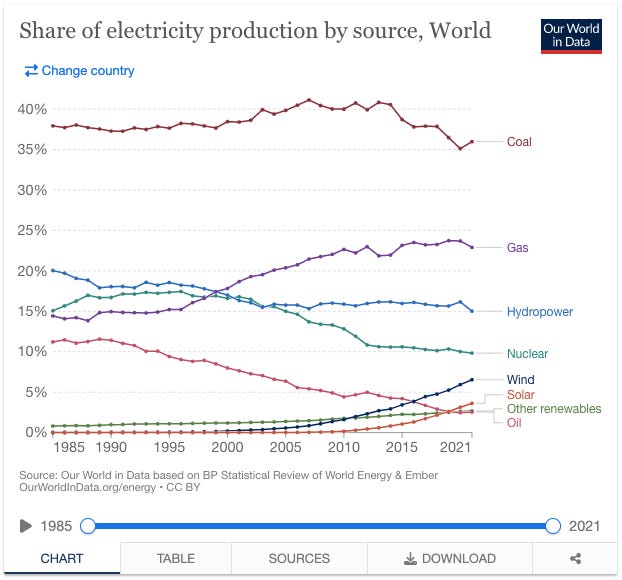

Throughout the book, the authors mention we’ve made great strides on reducing the cost of clean energy sources like solar and wind, and that we must get other ones onto the learning curve to scale them up. While that’s true, what they don’t mention is how far the world still has to go to reach net-zero. A better indicator is the total share of electricity production by source, which shows that renewables aren’t yet even close to dominating like they’ll soon need to. Speed and Scale’s OKR tracker also does a good job of breaking down the components of real progress from a global perspective, which you’ll see is currently all over the place.

Thus, my point here is that we need to see the bigger picture, rather than prematurely celebrate over the wrong pieces of information.

Americentrism

Defined as the tendency to view topics from an overly US-focused perspective, unfortunately this was the case for all climate solutions the authors proposed. While somewhat understandable given their likely audience, this is an area where Hal Harvey’s other book Designing Climate Solutions does a much better job. It in contrast includes case study examples from all over the world and all levels of government. Moreover, the policy principles he details like building in continuous improvement and reducing soft costs can more or less be applied anywhere as well.

Simply put, the authors appear to have written The Big Fix under the assumption that what works in the US will always work elsewhere too. However, it’s important to note that the political, economic, and geographic challenges those places face to implement climate policy are in reality unique to them.

Thus, it’s important to emphasize that people living outside the US in places like say, Japan or Russia, equally deserve answers on what they can do to advance climate solutions. Merely telling those living under a one party state to vote for example wouldn’t help much now would it? But unfortunately because of both author’s Americentric bias, this book doesn’t provide that as much as it certainly could’ve.

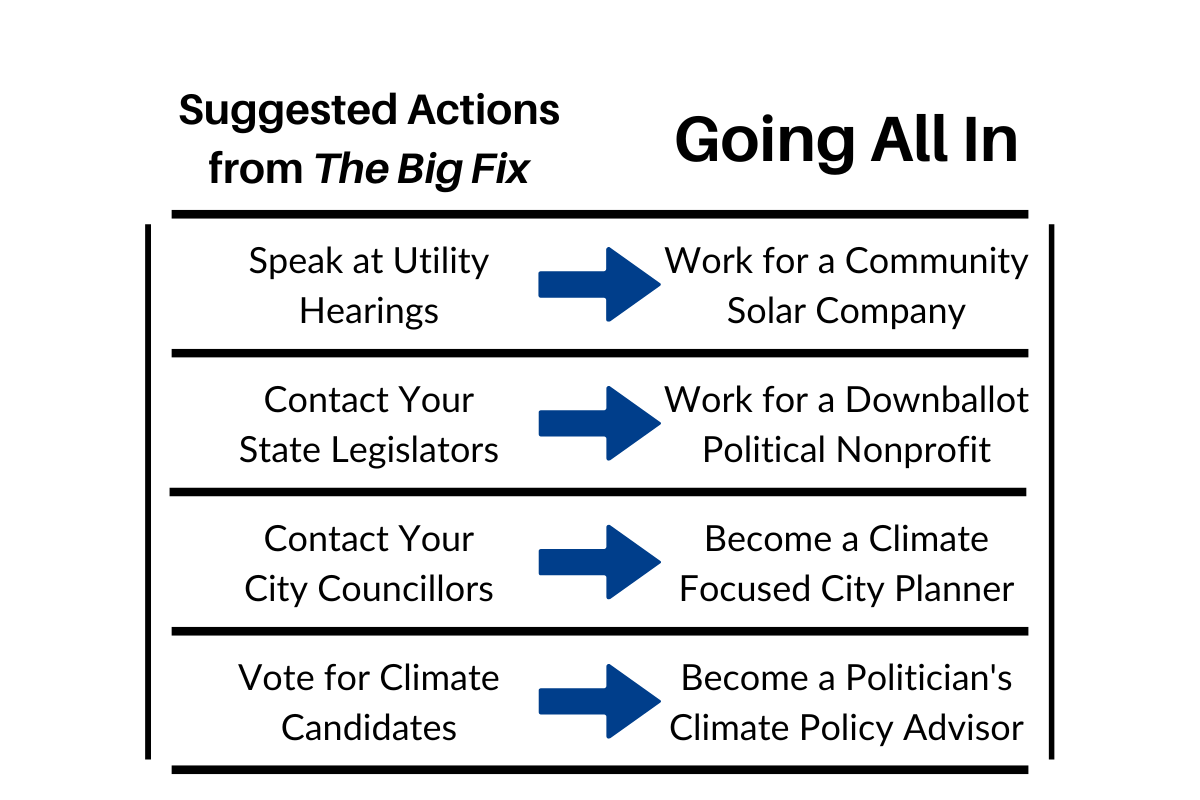

Stopping Short of Going All In

For people completely new to climate advocacy, the author’s recommendations under each of their “Pulling The Levers” sections are quite helpful. However, for those seeking more, this book sadly doesn’t go far enough. That’s because if you look closely, all of the suggested actions stop at volunteer advocacy; things like speaking up at utility hearings, contacting your state legislators, etc. While there’s of course nothing wrong with those, in reality many more aggressive options exist to pursue a career on the frontlines through spaces like nonprofits, think tanks, the private sector, or perhaps most prominently: doing what it takes to become a climate policymaker yourself.

From my perspective, the authors essentially wrote the book as if they assumed people will cut themselves off from going all in to help save the planet, without realizing for many the opposite is true. What’s even more frustrating is that Hal likely knows tons of people who could share strategies on how they make a significant impact, since his think tank Energy Innovation routinely delivers research findings to climate policymakers. Yet he doesn’t go into that at all.

For now, it seems like a book that thoroughly covers what careers in climate policy entail behind the scenes still doesn’t exist. Though maybe a certain someone will change that one day? Fingers crossed.

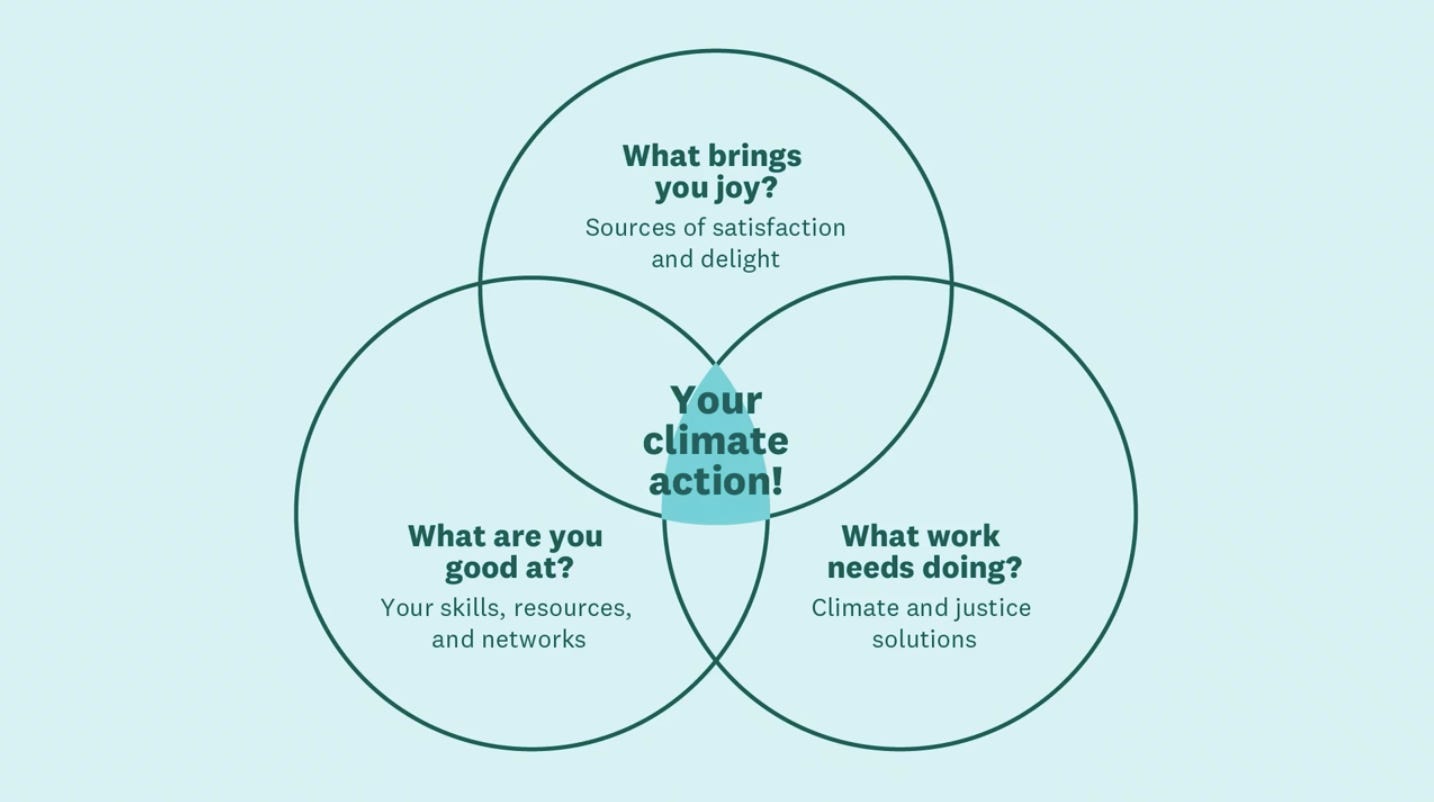

A Better Approach To Finding Your Style

So with that last part in mind, how do you actually determine which type of climate career is best? How to go further than stopping at volunteer advocacy? The answer of course will vary, but a great starting point I’d recommend is watching marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s TED Talk on the subject, then filling out her Venn diagram to use as future guidance.

A key point regarding your diagram is this: don’t be afraid to make your own climate opportunities when needed, rather than wait for them to come to you. You might realize there’s a specific issue not being addressed, or come up with a project idea that’d be the first of its kind. Just know in advance that your climate journey, whether you decide to pursue a career in it or not, likely won’t be easy at first, but will be worth it in the long run. Make sure you can tell your grandchildren you went all in to safeguard a livable world for them. What that looks like in practice until then is up to you.

“Planet Earth is miles outside its comfort zone; how many of us will go beyond ours?” –Bill McKibben

Calls to Action

- Create your own climate action Venn diagram covered in the TED Talk linked above. Brainstorm how you could potentially make your own opportunity to go all in to advance the cause.

- Think of someone who currently works in climate in any way, then reach out to them asking if you could schedule an informational meeting. Then ask them key questions like how they got started early on in their careers, what challenges they faced along the way, what advice they would give to you, etc.

- Have thoughts on any part of this longer newsletter piece? Let me know by replying through email or leaving a comment!

Member discussion