Deep Dive: The State of National U.S. Climate Policy in Early 2024

In This Absolute Must Read Edition

- A Color Coded Snapshot of Where National Policy Stands Now

- Recapping The Good, So-So, and Bad Regarding Recent Actions

- America’s Current Climate Rating Out of 5 Stars

- My Best Policy Proposals to Fix 3 Overlooked Code Red Climate Issues

With last November’s release of the eye opening report State of Climate Action 2023 that covers how the world is collectively doing on climate, I thought I’d do an in-depth breakdown of where the United States specifically stands, plus recommend some policy solutions myself for the top challenges going forward. After all, what’s agreed to globally at annual negotiation forums like COP28 always still needs to be implemented at the national level.

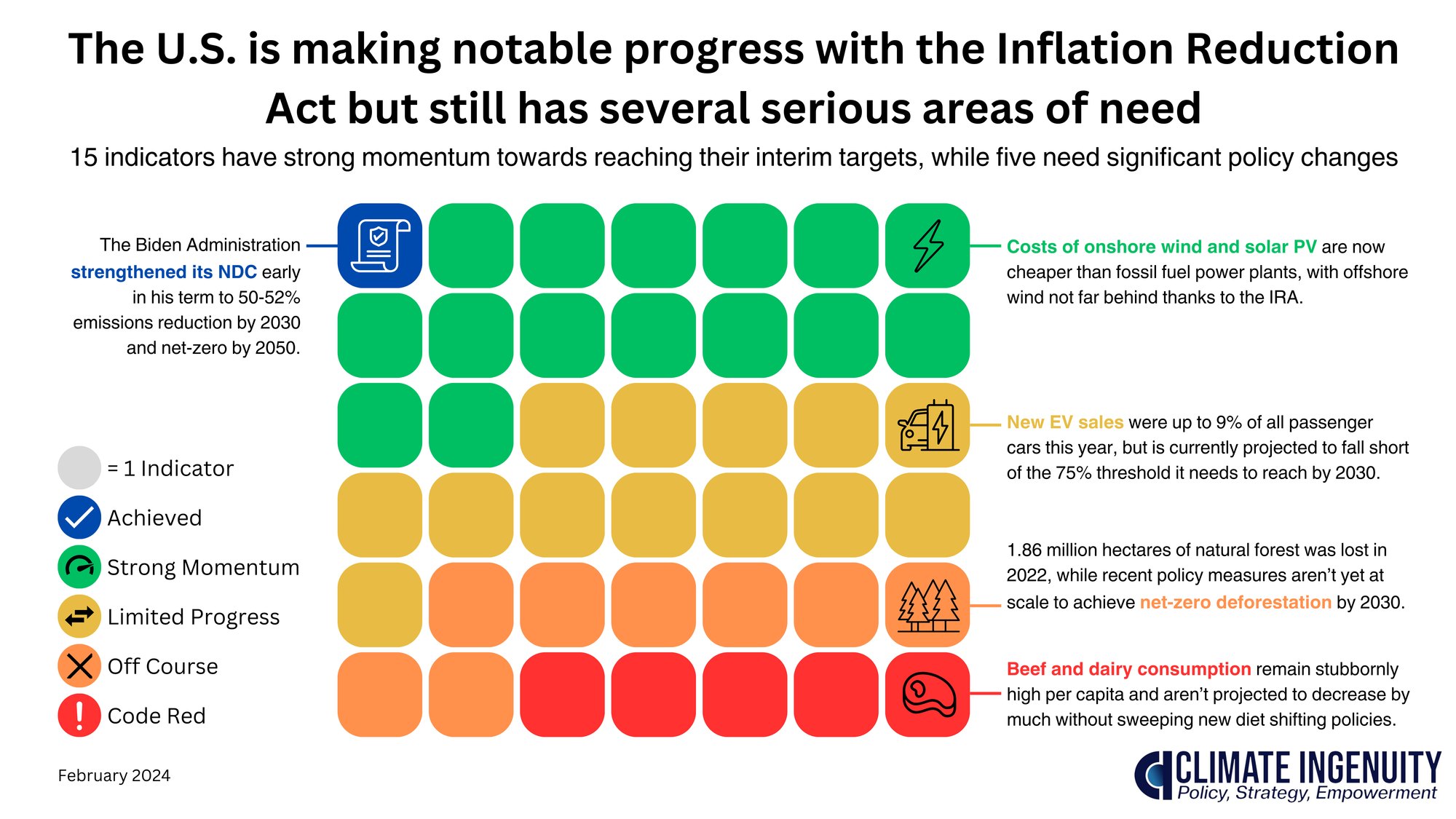

Thus, in order to properly assess where the U.S. is at rather than just rely on what I’ve personally heard about, I put together 42 policy indicators spanning each major sector and then some; the exact same number used in the report. I borrowed then adjusted most from the book Speed and Scale’s similar OKR tracker, but did add some of my own to account for country specific areas of need like permitting reform and critical minerals production. I also opted to use the same five status levels from said tracker, ranging from achieved at best, limited progress in the middle, to code red at worst.

After combing through numerous data sources, designing a color coded graphic, creating a second interactive webpage on the Climate Ingenuity platform to showcase my findings, and developing creative policy solutions for the top 3 most dire domestic issues, here’s what you need to know about where the world’s largest historical emitter currently stands in the fight against climate change:

Visual Overview of Key Policy Indicators

The types of indicators I used within the 42 total spanned themes like cost parity, market share, ending large emission sources, and carbon intensity, just to name a few. Most are also time bound with rising stringency for the metrics, just as all effective climate policies should be by default. Furthermore, I determined the statuses for each indicator based on up to two factors of equal weight: quantitative data and recent policy actions from the Biden administration, Congress, or both. Any information I could find on future projections was a plus.

Without further delay, below is the big picture snapshot. If you’re interested in seeing more details, including sources, please visit the main Climate Ingenuity platform.

The Good: Clean Energy Investments and Price Parity

It’s no secret: The Inflation Reduction Act has infused a historic amount of investment into clean energy across the country. The one fact that shows that best? Over $372 billion in new spending has happened since it passed alone; well on track to meet the target of ~$500 billion per year by 2025 the financial incentives indicator calls for.

What this especially helps with for climate though is reducing the cost of essential clean technologies compared to their fossil fuel counterparts. As the boost in funding helps their volume increase, their price will decrease thanks to the learning curve principle; a topic I’ve covered before in a previous edition.

Examples include:

- The maximum cost of onshore wind and solar PV are now cheaper than both gas and coal fired power plants.

- Average EV price from this past September was ~$15,000 lower than 2022.

- IRA’s $3/kg tax credit for green hydrogen could soon make it cheaper than gray hydrogen created using fossil gas.

Overall, the IRA is the primary reason why 12 of the 15 total indicators I marked as having strong momentum are that way, with executive action from the Biden administration helping with seven. The law could also potentially create over 9 million new clean energy jobs on its own by 2032 per one analysis.

The So-So: Market Shares, Industrial Decarbonization, and More

Market share is a very important indicator of how much sector specific climate solutions are displacing fossil fuels. In that category then, the U.S. has a long way to go. Clean electricity generation was about 40.5% as of 2022 and needs to reach 80% by 2030. EVs still only make up 9% of the new passenger car market. And sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) has barely gotten off the ground at just 0.1% of total jet fuel consumption.

For some areas like the power sector, there are clear barriers to faster deployment that must be addressed; permitting issues in that case. For others however, the pattern I see is that they’re unfortunately still in their early stages of development. Cases in point:

- SAF is essentially starting from scratch with moving down the aforementioned learning curve, as making it currently costs over twice as much as traditional jet fuel.

- A plan that addresses shipping, known as the National Blueprint for Transportation Decarbonization, was just released by federal agencies last year.

- A large chunk of recent policies aiming to help clean up industry are focused on research and development (R&D) support. In other words, the solutions most needed to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors like steel and cement aren’t yet ready at scale.

Personally speaking, I’ve never bought into the shallow idea that simply spending more money on everything (often in the form of voluntary grant programs) will fix all of America’s climate problems by itself. Effective climate policy design doesn’t work that way and there are far more aggressive options available. However, the concerning statistic to remember here is that President Biden’s FY 2024 budget only allocated around $11.3 billion for clean energy R&D specifically, while Speed and Scale’s relevant tracker calls for $40 billion per year. That’s nearly $30 billion in annual funding not tied to legislation being left unused that otherwise should go towards measures needed to help meet national climate targets. Those could include for example, additional buy clean procurement across even more of the industrial sector, challenges for companies to scale carbon-negative cement combined with stage-gating to boost cost competitiveness, etc.

Looking at the sustainability side of things, the Biden administration very recently announced right as I was researching for this edition their draft national strategy on reducing food waste, as well as their intent to soon ban logging in old-growth forests. Those are two areas with a lot of ground to make up, so hopefully the rules are finalized before the November election. Unfortunately, the same progress can’t be said yet about ending new fossil fuel projects. Although coal is on the decline, not only did the President controversially approve the Willow oil project last spring, but 26 new gas plants are planned for construction through 2025. That also doesn’t even include his now delayed decision on the CP2 LNG export terminal, which if later approved would emit significantly more than Willow.

The Bad: Chronic and Overlooked Issues

I remember first learning about the American food system’s impact on the environment back in middle school from both watching the documentary Food, Inc and reading The Omnivore’s Dilemma for homework. Unfortunately in the cases of beef consumption and nitrogen-based fertilizer use, both of which contribute to super-pollutant emissions far more harmful than carbon, the data shows things haven’t improved much in either area since then. The U.S. still consumes more beef than the other top four emitting countries combined at nearly 60 pounds per capita in 2022 (130 pounds for dairy). On the flip side, around 72 million tons of CO2e was emitted from nitrogen-based fertilizers in 2018 and to make matters worse, the IRA’s incentives for biofuels could actually increase its use going forward.

The former has been deemed by Politico as “The red meat issue Biden won’t touch” and so far has only been addressed around the margins like through feed additives or digester systems, without seeking to tackle the actual root of the problem. You can essentially think of it as one of several nationwide bad habits worsening the climate that will require difficult systemic changes to fix, with another one being the $754 billion indirect subsidies the government spent in 2022 bailing out the fossil fuel industry.

As for overlooked code red issues from the graphic, it turns out there is still no national scale plan to ensure all new buildings run cleanly with zero emissions. That means a sizable portion of buildings under construction can still be powered with fossil gas, which risks locking in a significant amount of emissions from the sector for years to come. Additionally, despite the progress made with annual sales of EVs and their price parity, less than 1% of total miles driven across the country was electric as of 2021. In other words, nearly all of the 2.9 trillion vehicle miles driven three years ago was powered by fossil fuels.

Now that’s a metric you won’t hear media outlets (let alone government officials) tout anytime soon, if they’re even aware of it to begin with.

Current Rating

Overall if you average out all of the indicators on a weighted 1-5 scale, then I give the U.S. ~3.7 stars on its national policies in early 2024. It’s clear the Biden administration is making climate action a higher priority than previous ones, yet there remains much more to be done, as is the nature of this field.

To stop writing here wouldn’t be right in my view though, knowing that the whole purpose of climate policy at its core is to deliver solutions effective enough to be 1.5C compatible. With that in mind, below are some of my best proposals to fix three of the most pressing code red issues in the tracker: EV miles driven, clean new buildings, and reducing beef consumption.

EV Miles Driven

Recommendation #1: Prioritize Switching Gasoline Superusers to EVs

Getting from <1% of total miles driven being electric to 50% by 2040 and 95% by 2050 is mainly a challenge of gasoline displacement. In other words, simply boosting new EV sales isn’t enough because stock turnover inherently takes a while. Fortunately, within this subsector climate policymakers can focus on switching gasoline superusers to EVs first.

First brought to light through a report by advocacy nonprofit Coltura, they found that the top 10% of U.S. drivers consume an outsized 32% of all gasoline for passenger cars, more than the bottom 60% of drivers combined. Moreover, there is a huge disconnect in the geographic distribution of EV adoption, since areas with lots of superusers who most need to make the switch tend to have low rates of going electric, and vice versa.

Thus, the policies needed to address this problem have one big theme in common: prioritization. As in the following:

- Replace flat EV incentives with ones tailored to superusers by tying their cost savings to the amount of gasoline displaced according to their car’s odometer reading.

- Scale public charging infrastructure in areas with the greatest concentration of superusers, especially high-speed ports along rural freeways and in small towns.

- Target superusers with EV consumer education campaigns based on the latest demographic data.

My last point there raises some questions, however, about how the federal government can encourage EV adoption in areas reluctant to make the switch. To overcome that, I’ve drawn upon a perhaps unexpected source of guidance: behavioral psychology.

Recommendation #2: Leverage Cutting Edge Messaging Strategies

A major obstacle to solving the electric miles driven issue through the gasoline superusers approach is how EV adoption has been much slower in red states. There are many reasons for this of course, but based on the book The Catalyst published in 2020 by University of Pennsylvania professor Jonah Berger, hold ups in general can roughly be split into a few categories: reactance, endowment, distance, uncertainty, and corroborating evidence. In simple terms, those mean:

- Reactance – people push back when pushed on their decisions.

- Endowment – people stick to the status quo until shown strong reason(s) not to.

- Distance – people disregard viewpoints that are too different from their own.

- Uncertainty – people really dislike and avoid risk.

- Corroborating Evidence – people sometimes need proof from multiple sources at once to change their strongest viewpoints.

With all that in mind, it makes complete sense why simply pushing harder about how great EVs are isn’t enough to override mental blocks tied to both human nature and political ideology. The good news is there are better messaging strategies that, if combined with existing efforts to improve price performance parity, charging infrastructure, battery storage, etc, can move the needle both at scale and in a way where previously reluctant consumers decide to switch to EVs themselves. Working with stakeholders like state transportation agencies and car dealerships to make said strategies mainstream, national policymakers can implement the following:

- Highlight the attitude-behavior disconnect – showcase instances where consumer attitudes align with buying an EV, but real world behavior doesn’t.

- Reframe the status quo – highlight the hidden costs of sticking to gasoline cars, like high fuel prices, maintenance expenses, and air pollution. Then frame EV adoption as a way to regain losses incurred by those downsides.

- Find common ground – identify shared values like local job creation and energy independence that resonate across the political spectrum, then frame EV adoption as a unifying action aligned with those mutual interests.

- Drive discovery – run campaigns targeting consumers who haven’t considered switching to EVs before, highlighting the benefits and addressing common misconceptions. Use creative, low-commitment engagement methods like interactive simulations and local meetups to spark interest.

- Leverage diverse testimonials – curate testimonials from various sources like local public figures, community members, and transportation experts that showcase their positive experiences with EVs. Then concentrate them in a cohesive narrative to reinforce credibility and demonstrate consensus.

Recommendation #3: Scale Engine Retrofitting

It’s clear scaling EV adoption is essential to meeting national climate goals, especially if gasoline superusers switch first. More convenient though would be to skip that step by allowing drivers to keep their existing cars without burning more fossil fuels, through a less well known solution called engine retrofitting. This approach of swapping all relevant vehicle parts from gas-powered to electric also has several broader co-benefits according to conversion company Blue Dot Motorworks, such as reducing the amount of EVs, batteries, and chargers needed nationwide to stay under a 1.5C compatible carbon budget.

Thus, policies I’d recommend to help quickly get this early stage technology up to market scale include but aren’t limited to:

- Allocate R&D spending for engine retrofitting startup companies in next fiscal year’s budget (which should be more than tripled anyway as mentioned earlier).

- Include engine retrofitting the next time President Biden invokes the Defense Production Act or equivalent.

- Create IRA style grant programs that relevant companies could be eligible for based on their technology’s price performance parity compared to simply buying a new EV.

- Require all new cars to be retrofit compatible by 2025.

Recommendation #4: Offer “EPIC” Incentives

EPICs stand for extreme positive incentives for change. The term, emphasized in 2022 published book Supercharge Me, centers around prioritizing incentives that greatly reduce the price of substitutes to fossil fuels, rather than “sticks” like carbon taxes that are prone to trigger resistance. A key example would be tax exemptions, in which consumers could purchase an EV without needing to pay sales tax on it.

Along those lines then, EPICs can and should be incorporated into all three of my previous policy recommendations, knowing they build on the incentive-based approach the Biden administration already favors. Apply them to gasoline superusers. Apply them to make engine retrofits more affordable. Publicize them widely. Tailor them to encourage drivers of the oldest or least efficient gas cars to switch. The possibilities go on.

Clean New Buildings

Ideally to achieve this indicator, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could simply mandate all new buildings to be zero emissions in operation by 2030. Unfortunately, building codes are mostly handled at the subnational level, which likely makes such a measure out of the agency’s regulatory scope and rules out setting a binding national target for the same reason. Thus, some workarounds are needed, which I’ve divided here into two themes:

The Foundation: Set a Strong National Definition, Goal, and Strategy

Recently, the Biden administration released their draft national definition for zero-emissions buildings. It states that they should be highly efficient, free of on-site emissions from energy use, and powered solely from clean sources.

The next step then is to establish a national goal on this front, which serves multiple purposes at once:

- It sends a signal that addressing this issue is a priority to President Biden.

- It provides a better sense of direction for subnational governments and key stakeholders to follow, in lieu of setting a binding target.

- It allows flexibility for subnational governments to tailor implementation strategies according to their specific needs and circumstances.

Putting this together, a national strategy ensures the goal comes with a roadmap for proper implementation. Even better, it leans into an approach the administration has already taken with other climate issues mentioned earlier, such as transportation, methane emissions, and food waste.

The Details: Smart Incentives, Stakeholder Engagement, and Workforce Development

Without a mandate, it’s essential for the national strategy I’m proposing to focus on removing as many barriers as possible to implementation. After digging through a 120+ page report on this topic by Climate Action Tracker, I found that the main barrier types to scaling clean buildings include upfront cost, perceived risk, and lack of awareness. Conventional methods like offering grants and loans can help with the first two, but they have their tradeoffs. Fortunately, the federal government can overcome those by developing all-in-one financial support packages for zero emissions building construction, then offering them through a new green bank.

Providing a mix of finance methods from both public and private sector sources that also includes credit risk guarantees, low-cost debt, and performance-based debt-relief holds a number of co-benefits as well. Specifically:

- It leverages private finance for a targeted purpose within the climate space, reducing the total capital needed from public sources.

- It can get the financial sector accustomed to the type of projects they’ll be asked to cover long-term, which reduces perceived risk on their end.

- It lets borrowers avoid needing to use different funding sources for the same project.

The obvious following measure then is to raise awareness of this new innovative policy, similar to how prominent Biden administration officials have touted the IRA’s climate provisions across the country. Even the best incentives won’t move the needle if no one knows about them, so it’s crucial to fund effective communication campaigns that highlight the various benefits of committing to all clean new buildings vs locking in more emissions from fossil fuels. Policymakers could also repurpose the same behavioral psychology-based strategies I discussed earlier regarding EV adoption to get buy-in from reluctant stakeholders, such as organizing industry roundtables as corroborating evidence for the incentive packages.

Stakeholder engagement matters here due to the large number of different relationships and roles various actors play in the buildings sector as a whole. To achieve the required pace of change then, each of them must be properly engaged simultaneously. Per the aforementioned report, I identified four policy areas that I believe should be prioritized on this front. Those are:

- Multi-level governance – leverage the natural advantages of different levels of government to maximize potential impact, such as combining federal funding with local implementation.

- One-stop-shops – offer trusted information and resources to relevant stakeholders on technological, finance, and contracting options. A comparable platform would be the Inflation Reduction Act Guidebook the White House provides on their website.

- Capacity building – ensure commercial banks and financial institutions have the internal know-how they need to offer the all-in-one financial support packages as discussed earlier.

- Inclusive dialogue – facilitate a just transition by ensuring diverse voices are heard in the engagement process, including government, developers, installers, and the private sector.

Regarding workforce development, the main thing that needs to happen is investing in training programs for skilled installers. One example of this is how Spain’s Construye 2020 project offers “green courses” for construction professionals on renewable energy and energy efficiency. As a related co-benefit, providing retraining in modern climate-friendly technologies prevents building contractors from being left behind as the market shifts away from fossil fuels, essentially future-proofing them from an employment standpoint.

Reduce Beef Consumption

This last issue is particularly difficult because policies that address it must both not cause public backlash in an election year and be ones Democratic leaders could actually be willing to do. Nonetheless, there is a path forward that revolves around one specific objective: shifting consumer choices.

Recommendation #1: Target Beef “Super Consumers”

A study from last year covered by The Guardian revealed that merely 12% of the U.S. population consumes half the beef. Primarily being men and those between ages 50 and 65, this “beef super consumers” trend presents a challenging opportunity: getting them on board would make an enormous difference, but they might be the hardest ones to change, if not also hostile to it. Fortunately, the same behavioral psychology strategies I discussed earlier regarding EV adoption can be applied here as well.

In the government’s public messaging strategy on this issue, they can advocate for smaller steps that increase with time (known as chunking the change), while developing a way to measure progress towards the interim goal of reducing beef consumption 25% by 2030. Another way is to find unsticking points by emphasizing shared values this demographic nonetheless has with fighting climate change, such as boosting economic growth, innovation, and overall quality of life. Further policies will also be needed to prevent the younger generation from becoming beef super consumers themselves later on, such as procuring plant-based alternatives in public schools.

Recommendation #2: Boost Plant-Based Meat’s Popularity

The solution that naturally goes alongside the one above then is to make plant-based alternatives significantly more popular, knowing they only comprised 1.3% of the U.S. market in 2022 per the State of Climate Action report. While there aren’t yet many real-world case studies of this being done successfully through policy changes, scalable tactics can be built around a different behavioral psychology book’s recommendations, Contagious: Why Things Catch On, again by Jonah Berger. Those could include:

- Strategic Placement – work with relevant stakeholders to prominently display plant-based alternatives or offer them as specials at a nationwide scale, creating mental triggers that remind consumers to consider these options more often when making food choices.

- Visibility Initiatives – support efforts to increase the visibility of plant-based alternatives in public spaces since products designed to be showcased tend to gain more traction in the marketplace.

- Partnerships with NGOs – collaborate with nonprofit organizations to amplify the practical value of plant-based alternatives and their impact on broader societal goals like combating climate change.

Recommendation #3: Research Climate Labeling

Lastly, placing traffic light style climate impact labels on food items could potentially be a game changing policy solution, given that it would uncover the substantially higher emissions of beef as measured by CO2e intensity. However, not enough research or studies have been done to show how much it would actually make a difference. Further complicating matters is how consumers may justify and rationalize eating beef anyway despite being aware of its harmful effects on the climate, a term a New Republic article calls the “meat paradox”. Thus, the best way to know for sure is to fund an official government-backed research study on the topic, paying close attention to how this option can maximize effectiveness while also minimizing potential risk regarding public opinion. Once that’s completed, national policymakers can then decide on next steps, which may involve trying it out for a short amount of time and/or doing a public comment period much like other existing climate provisions the administration has already begun implementing.

What’s Next

After two post-covid years of U.S. emissions slightly increasing, Rhodium Group recently reported that it finally decreased by 2% in 2023. Knowing effective climate policies tend to compound in impact over time, you can essentially attribute much of that to IRA implementation growing pains as federal agencies ironed out the details. Going forward, I believe all new measures need to strike a balance between being visionary while still grounded in proven principles, much like the ones I’ve put together in this edition. As for my closing thoughts, here’s to hoping President Biden wins re-election in November despite his administration’s imperfections, that Democrats regain a majority in both chambers of Congress, and perhaps that yours truly can play a bigger role in making the next piece of groundbreaking climate legislation happen.

There simply is no more time to lose.

Member discussion